Spoleto Review: Taking a page from Virgil in an absorbing new work

"The Song of Rome" toggles from past to present to contemplate democracy

Editor’s note: This review was first published in Charleston City Paper.

If there is just one takeaway from an epic poem — and a cogent new play concerning one — it’s the unbearable lightness of a republic.

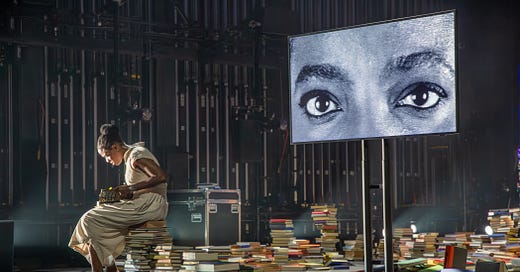

Such is the thrust of “The Song of Rome,” which will likely send a Sisyphean shudder through anyone invested in the fate of democracy. And, on the Dock Street Theatre stage, it’s doing so by loading heaps of books, real-time black-and-white projections and probing, albeit inconvenient truths.

Part of the 2024 Spoleto Festival USA, the world premiere work penned by Denis O’Hare and Lisa Peterson, which is directed by Peterson, brings the collaborators back on the heels of a rave reception for “An Iliad.” The one-man-show on the 2023 program starring O’Hare offered contemporary context to Homer’s epic poem, by way of rendering real the ever-mounting body count of the Trojan War.

“The Song of Rome” chases that with another enduring poem. Both are bound together by history, as the Roman poet Virgil took a page from Homer’s epic, using it as the basis for “The Aeneid,” which charts the journey of Aeneus, a refugee of the Trojan War headed from Troy to Rome to dream up a new republic.

This time Homer’s Coat, as the collaboration is called, devised a two-hander that avails of the considerable command of actors Rachel Christopher and Hadi Tabbal. The two toggle between Roman toga times and a present-day library at Emery University in Atlanta. Together, they revisit a republic past to better grasp today’s power grabs, global shifts and gender dynamics, absorbing the audience throughout.

It is books — dusty and worn, detailing the rise and fall of empires–that connect the play’s two timeframes. A spare stage houses towering stacks of vintage tomes. They live alongside AV equipment and reach back upstage to a blackened wall, compliments of scenic designer Rachel Hauck, setting the tone for jaunting back and forth from past to present political jockeying.

The actors each portray three corresponding roles. For starters, Christopher is The Girl, seen in projections via both an on-stage screen and an upstage wall, with a counterpart in Tabbal’s The Man. They are also, respectively, Octavia, the sister of Augustus Caesar (aka Octavian), and Virgil, who is summoned to pen a poem, commissioned by the would-be emperor himself.

In the present-day, Christopher portrays Sheree, an undergraduate frantic to get up to speed on these classics for an exam. Tabbal is her tutor, Azem, a Syrian scholar who has recently arrived in America and who is desperately seeking asylum.

The parallels between patron and poet, teacher and student, assert themselves readily. Both Virgil and Azem are refugees, pointing up that forced migration dates back millennia, no matter the vaunted freedom bandied about in democracy now and way back when. The former, Virgil, was cast out of Rome, then enlisted by the very forces responsible for his ouster to spin heroic those Roman exploits, or latter-day propaganda. As Azem, the actor brings to the American shores his character’s scholarship on such history, and its takeaways, including its parallels with our own fraying nation.

The plight of the refugee is chief among them. Virgil frets about how to manage his patron’s agenda while aiming to make the sort of art to secure his own immortality, but with one eye trained on remedying his cast-off, down-and-out lot in life. Azem engages in plenty of hand-wringing, too, knowing his fate is hanging in the balance of a green card and anxiously appealing to his student for help in that mission.

Through Christopher’s roles, we also see both worlds through the female gaze. With Octavia acting as liaison for Augustus (or Octavian as she calls him), we gain a less frequently observed female perspective on life with Augustus and company. She navigates her diminished status as a female in the empire, sucking it up and marrying Mark Antony for the good of the cause.

“The Song of Rome” then conjures a contemporary foil in Sheree. As a Black American woman, she is a descendent of the enslaved that were part of a mass forced migration, one that informed and continues to inform this republic.

Sheree is particularly effective in breathing new life and candor into such age-old gender oppression, countering historical facts with her modern-day shade, and frequently infusing offhand humor and vibrancy into her hot takes. Aghast at the likes of Dido et al, she parses tales of Cupid’s arrow. likening such Gods-sport to getting slipped a rufi.

Deftly crafted and superbly acted, “The Song of Rome” metes out boatloads of history, but in a way that goes down remarkably easily. Time and again it illuminates how past and present inform one another, even if they don’t change outcomes. Revisiting how a republic that was once so formidable dissolved in short order, Azem asks of Sheree, how long will it be until that happens in your country?

Back in Rome, when it dawns on Octavia that she is no longer living in a republic, she seeks to glean the reason, landing on, “It was killed by a hundred little incivilities and lies.”

True that. In “The Song of Rome,” it makes for a cautionary tale, and meaninginful evening of theater. It is well worth a visit to the Dock Street, where it is writ Latin and large in an epic poem.