When Tubman took the Combahee: An S.C. raid powers Gibbes exhibition

Repost from Charleston City Paper

Most anyone knows that Harriet Tubman served as spy, soldier, nurse and North Star navigator during the Civil War. And most know she fearlessly returned to the scene of her bondage to guide the similarly enslaved to freedom. Still, much about her eludes full grasp, particularly for historians who like their facts sufficiently sourced.

That is, until Dr. Edda Fields-Black found a way.

For years, the Carnegie Mellon University historian has trained her fastidious intellect on facts surrounding a South Carolina chapter of Tubman’s life, the Combahee River Raid. The Union military operation that took place June 1–2, 1863, freed 756 enslaved people along the river, burning several rice plantations along the way.

The yield of the scholar’s considerable rigor is COMBEE: Harriet Tubman, the Combahee River Raid, and Black Freedom during the Civil War, a 776-page eye-opener of an opus published by Oxford University Press in 2024.

On May 5, Fields-Black received the Pulitzer Prize in History for the work. The recognition resonates with her in how it gives voice to the experiences of hundreds of thousands of enslaved individuals.

“This is a South Carolina story, but one with national significance,” Fields-Black told the Charleston City Paper in the days following the Pulitzer announcement. She added that it is the antebellum history of Colleton and Beaufort counties, as many of those records were burned by Sherman.

Picturing an exhibition

The Gibbes Museum of Art on May 23 will further the groundbreaking work through a new exhibition, Picturing Freedom: Harriet Tubman and the Combahee River Raid.

Guest-curated by Dr. Vanessa Thaxton-Ward, director of Hampton University Museum who previously served as director of the Penn Center on St. Helena Island, it represents a collaboration with environmental photographer and Charleston native J Henry Fair.

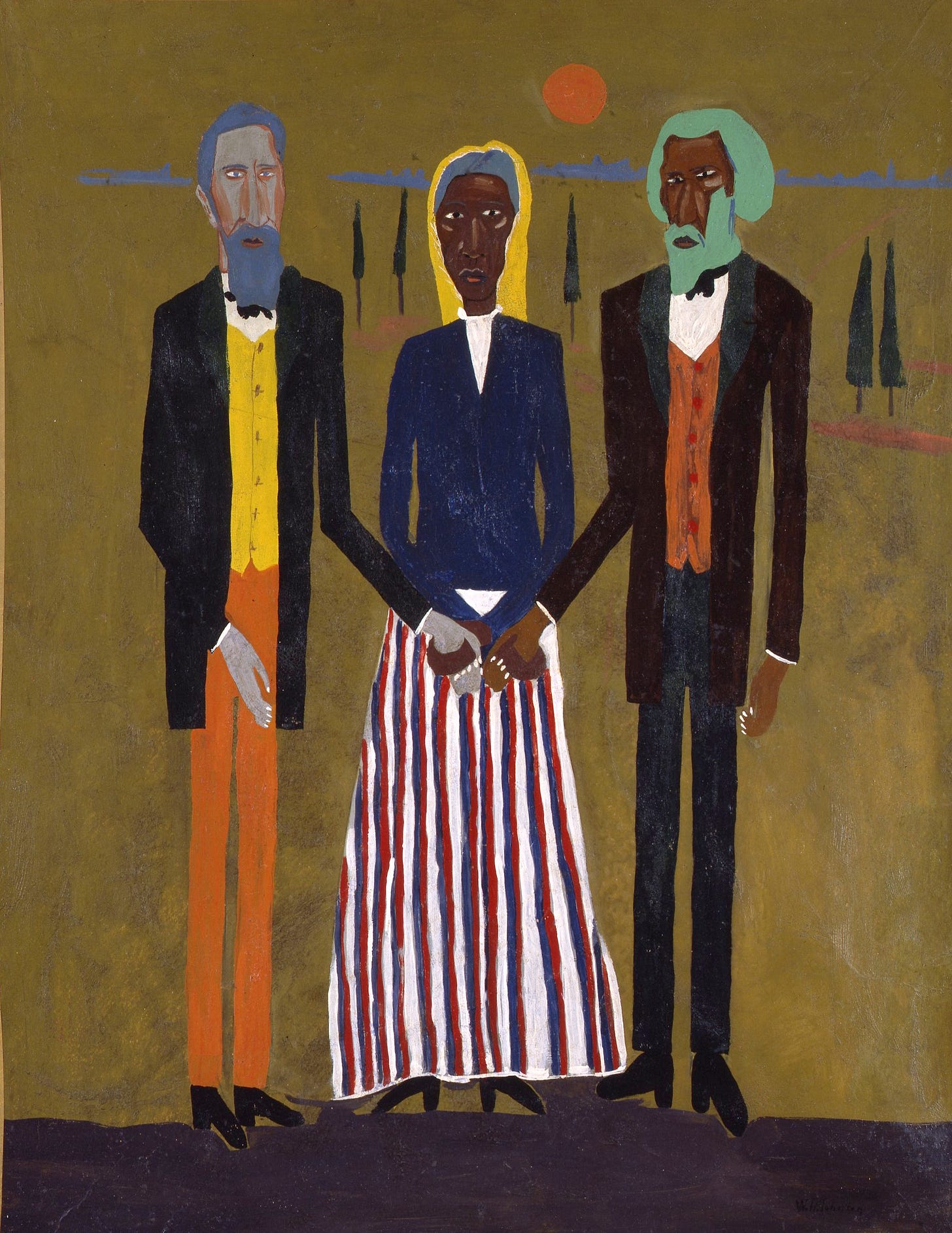

A visually layered foray into this seminal story, the exhibition features Fair’s large-scale photographs, works inspired by Tubman, including William H. Johnson’s 1945 “Three Freedom Fighters” and James DeLoache’s 1959 “Portrait of Harriet Tubman.” Also included are related artifacts and a video produced by Fair that features performer and educator Ron Daise (Gullah Gullah Island).

“A fascinating and scholarly undertaking by Dr. Fields-Black, I feel that those individuals who are not immediately drawn to a thick history book will find the exhibition an inspiration to then actually read the book for all of the details,” said Thaxton-Ward.

An untapped source

In her research, Fields-Black frequently followed the money. Accessing U.S. Civil War pension files, she was able to piece together the facts surrounding the enslaved and their families, their enslavers and the rice plantations where they labored, all to more fully assemble the narrative around Tubman’s Civil War service and the Combahee Raid.

“I knew that the pension files hadn’t been used in this way, and historians really hadn’t paid attention to them,” she said.

Other records, too, are transactional: newspaper advertisements for the sale of the enslaved; mortgages of planter names like Heyward, Middleton, Kirkland and Lowndes; wills inking the destinies of those in bondage, often filed in Charleston.

Through these documents and more, she was able to find the pulse coursing through the perfunctory paper trail, fleshing out seemingly dry-as-bone data to find personal accounts, in the voices of those relaying them – in other words, the human lives submerged between the lines. Name by name, she identified those who toiled in the face of disease and more, often in rice fields, always against their will – to then track how Tubman galvanized them into a high-stakes, do-or-die, successful military operation.

The importance of terrain

Mapping such terrain is no walk in the park, then or now, figuratively or physically. It is a snake- and alligator-infested, mosquito-stinging slog through the swamp. With her academic focus on rice culture and cultivation, Fields-Black has logged ample time there. In the book, she observes it was a proposition likely challenging for Tubman, who was accustomed to Maryland’s Eastern Shore.

It was something she felt essential to the story.

“For me, it’s experiencing the land, and walking on the ground and getting to know the river and the critters and the rice fields,” she said.

Enter Fair. Both the historian and photographer have ties to the upper Combahee, and current landowners up and down the river. The former’s great-great-great-grandfather Hector Fields fought in the raid; Fair is a descendant of Heyward family.

If the author’s vocation grounds her in the granular, Fair’s is expansive. His aerial shots are often obtained from a Cessna run by the Asheville-based nonprofit aviator outfit SouthWings. The images show the curls of the Combahee River, where the 2nd South Carolina Volunteers landed, and the causeway where they marched to Cypress Plantation.

Such synergy with artists has helped Fields-Black discover how she wanted to write history, and with Fair offered artistic interpretations of Tubman’s life and the Combahee River Raid.

“We saw the complementarity of the work and that’s something that drew us together,” she said. “I think it really energized both the book and the exhibit. … It was just irresistible.”

Fair was compelled to work on a project concerned with the topics the book addresses. “This systemic racism is hindering us as a nation,” he said.

Going from page to gallery wall started with Angela Mack, the Gibbes Museum of Art’s president and CEO. Up through Oct. 5, it’s the final exhibition in a 43-year tenure for Mack, who is retiring that month.

“She said ‘ I don’t want to do a book on the wall.’ ” Fair recalled. “And she was, of course, right.”

Mack said she was enthusiastic on first learning of the book.

“At the Gibbes, we are always interested in new research and compelling stories that broaden our understanding of a time and place in American art history. The publication of Dr. Fields Black’s book has offered this opportunity,” she said.

For Fields-Black, there is no time like the present for museums like the Gibbes to stay close to their values, support artists and historians–and to have their backs when they tell these stories that need to be told.

“It’s always important, but I do think it’s important now — more than ever.”

Thank you for letting us know about this exhibit! I have waited for years to know this story.i am looking forward to reading all 700+ pages.